Here’s your text revised for NZ spelling, grammar, flow, and AP-style short paragraphs:

I can only speak with any assuredness of myself here.

I am aware that at times I read the Scriptures as though I am watching a movie. Everything is happening on a screen, and I am in the audience — even when the audience is only me.

Admittedly, such a stance provides safety and security. Not getting directly involved offers protection.

The Gospel Context

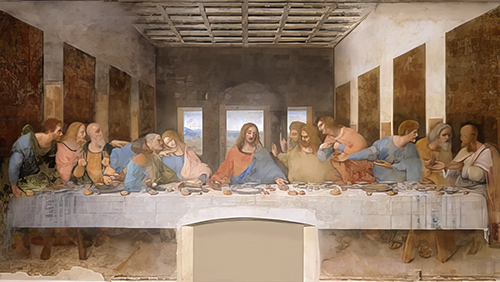

Our Gospel for this Sunday is commonly referred to as the Transfiguration. As a feast day in the Roman calendar, the celebration occurs on 6 August.

Each of the Synoptic Gospels — Matthew, Mark, and Luke — provides an account. Today, we read from Matthew 17:1–9.

A Striking Perspective

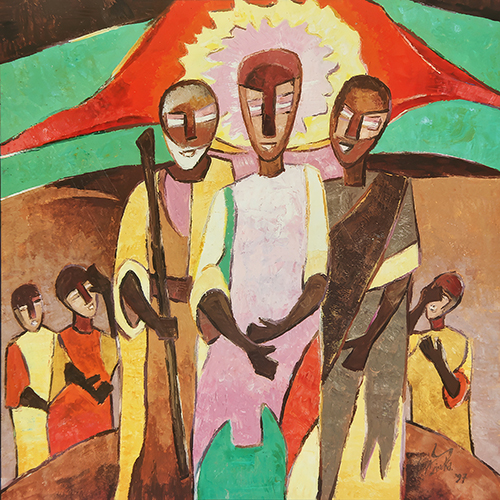

The image I have chosen is by Nigerian artist Augustin Kolawole Olayinka (1964–). The painting is titled The Transfiguration of Jesus.

The perspective is striking compared to most representations. The foreground does not show the disciples kneeling, but rather Jesus coming towards the viewer, followed by Moses and Elijah.

Three disciples stand further down the mountain in the background. They see the apparition only from behind — looking at the back of the divine reality.

Two of them hold a hand in front of their eyes to protect themselves from the blinding light.

Symbolism in the Details

Moses and Elijah do not stand next to Jesus in conversation; they walk behind him as his followers.

Moses carries the staff he used to perform miracles and the belt of the Passover. Elijah wears a simple prophet’s robe of camel hair, while the flames at the bottom of his robe may refer to God’s miraculous fire on Mount Carmel.

The colour scheme is striking, dominated by warm earth tones of brown and ochre. The green and red of the sky are reflected in the garments of Jesus, while his halo and the upper part of his robe are pink.

A Call to Engagement

In the artist’s perspective, the Transfiguration is not just about Jesus revealing himself to the disciples. Jesus comes towards us — I can no longer sit and gaze only.

Jesus invites me to engage, to commit, and to follow him. He asks me to join his followers across different ages — those who have been, those who are, and those who will be.

Discipleship calls for engagement and commitment, not observation.

Getting Up Without Fear

Towards the end of our Gospel passage we read: “But Jesus came and touched them, saying, ‘Get up and do not be afraid.'”

Many have indeed got up over the years to place their abilities at the service of their faith community.

This includes service on the parish pastoral council, ministers of the Word and the Eucharist, musicians, funeral teams, and those involved in the family Mass.

It also includes the “unseen” people — those who count the collection, tend the flowers, and care for the sacristy. Each has responded to the invitation of Jesus: “Get up and do not be afraid.”