This Sunday’s Gospel from St Luke (Lk. 14: 25 – 33) is one that I as a preacher run a mile from.

First, I am instructed to “hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself,” in order to become a disciple.

But wait!

There is more, “whoever does not carry the cross and follow me cannot be my disciple.”

How to win friends and gain followers!

Commentators rush to explain that the Semitic expression “hate father and mother” does not actually mean that in English.

It means “to love less.”

So why do English translations still say “hate”?

Literal translation often sounds absurd.

What is behind the Semitic expression is no less real – at times belonging to Jesus will mean difficult decisions.

And then, too, we are called to carry our cross!

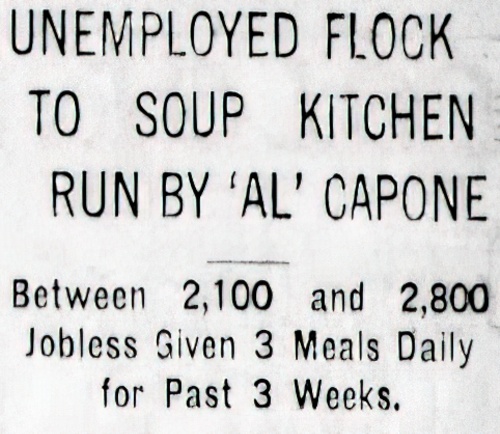

I remember well a news item in the New Zealand media in the year 2016 of a man taking a cross the length of the country.

In an interview the husband and wife explained “We’re walking the length of New Zealand with the cross and sharing the gospel along the way to those who would like to hear,”

If you look carefully at the illustration, what you notice is that at the foot end of the cross there is a wheel!

I am not wanting to deride the individual in any way, however, I do wonder if there is another Semitic expression I have missed that somehow translates ‘carry’ to ‘wheel’?

I am reminded of the story of the king and queen visiting the monastery of the great Zen master, Lin Chi.

They were astonished to learn that there were more than 10,000 monks living there.

Wishing to know the exact number, they asked, ‘How many disciples do you have?’

‘Four or five,’ Lin Chi replied.