The township of Pukekohe lies some 45km south of Auckland city in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

In the township, there is a store called Pik n Mix. It’s an online lolly store with over 400 different types of loose lollies.

Yes, you read right – 400!

When purchasing, you need to make a choice. Is it the size, the colour, or the taste that influences your choice of lolly?

What you choose and pay for then becomes your responsibility.

This simple act of choosing mirrors a deeper spiritual truth.

In our First Reading today (Ecclesiasticus 15:16–21), the author invites us to make a choice.

“God has set fire and water before you; put out your hand to whichever you prefer. People have life and death before them; whichever a person likes better will be given to them.”

God summons us to a radical way of living. We are called to be more than just moral: God invites us to be virtuous.

We become virtuous by habitually choosing to do good.

Naturally, we are not perfect. However, God calls us to reflect on how we live and to understand what has gone right and what has gone wrong for us.

Such reflection can lead us to insight that will help us to live better and be virtuous in the future.

Therefore, by reflecting on our experiences in the light of our faith, we grow in wisdom.

The author of today’s first reading, Sirach, affirms that God knows every human action. St. Paul reminds us that God has many riches for those who love him.

Jesus, in Matthew’s Gospel, says that he has come not to abolish but to fulfil the Law and the Prophets.

What we see clearly in the readings today is that there are repercussions – good or bad – for all our actions.

Our challenge is to avoid opportunities that do harm and to choose those that lead us to God.

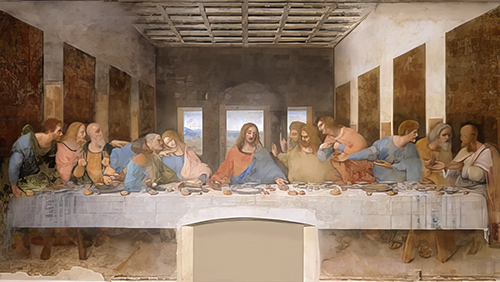

Sirach, the Psalmist, Paul and Jesus embraced this way of life. They are examples of how we can become virtuous and wise.

If we take to heart their messages from the readings this Sunday, we too, like them, will be true beacons of virtue – people of faith, hope and love.