Jesus is thirty years old when his baptism happens.

According to Mark’s Gospel, he has not said a single word up to now!

Maybe, that is the focal point of Baptism.

Not the washing away of original sin, rather being “dipped into” (the original meaning of the word, Baptism) the never-ending love of my God.

“And a voice came from heaven, ‘You are my Son, the beloved’” (Lk 3:22)

Until we “know” we’re a beloved son or beloved daughter, we don’t have anything to say.

We can “know” a chocolate cake by reading the recipe.

We can also “know” a chocolate cake by taking a bite of one. And once we have taken a bite, we won’t stop talking about it.

In his baptism, Jesus was dipped in the unifying mystery of life and death and love. That’s where it all begins—even for him!

The unique Son of God had to hear it with his own ears and then he couldn’t be stopped.

Then he has plenty to say for the next three years, because he has finally found his own soul, his own identity, and his own life’s purpose.

Might the only purpose of the gospel, and even religion, be to communicate that one and eternal truth.

You are a beloved daughter or son of God.

The illustration I have chosen might well appear a little confusing at first.

The illustration is titled Baptism of the Lord (Epiphany).

It was produced in the XVII century by the Orthodox dispensation in Greece and is housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Swimming in the river Jordan are fish. It is quite natural to have a river with fish.

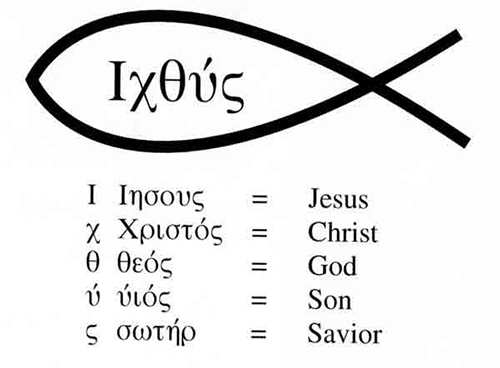

Also, let us recall one of the oldest images of Christ and his followers was indeed the fish.

The dominant language of the early Church was Greek, and in Greek the phrase “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior” produced the acronym ICHTHYS, the Greek word for fish.

An ancient symbol of Christianity carved on the wall of the cave used as a chapel by the seventh century St. Fillan in Pittenweem, Fife, Scotland”