In Aotearoa Maori culture, meeting houses (whare nui or whare puni) are symbols of tribal prestige and are often named after, and seen as the embodiment of, a tribal ancestor. The structure itself is seen as an outstretched body, with the roof’s apex at the front of the house representing the ancestor’s head. The main ridge beam represents the backbone, the diagonal bargeboards which lead out from the roof are the arms and the lower ends of the bargeboards divide to represent fingers. Inside, the centre pole ( poutokomanawa) is seen as the heart, the rafters reflects the ancestor’s ribs, and the interior is the ancestor’s chest and stomach. Whare are richly carved, and these carvings will be particular to the local tribe (iwi), and will declare “this is our house”.

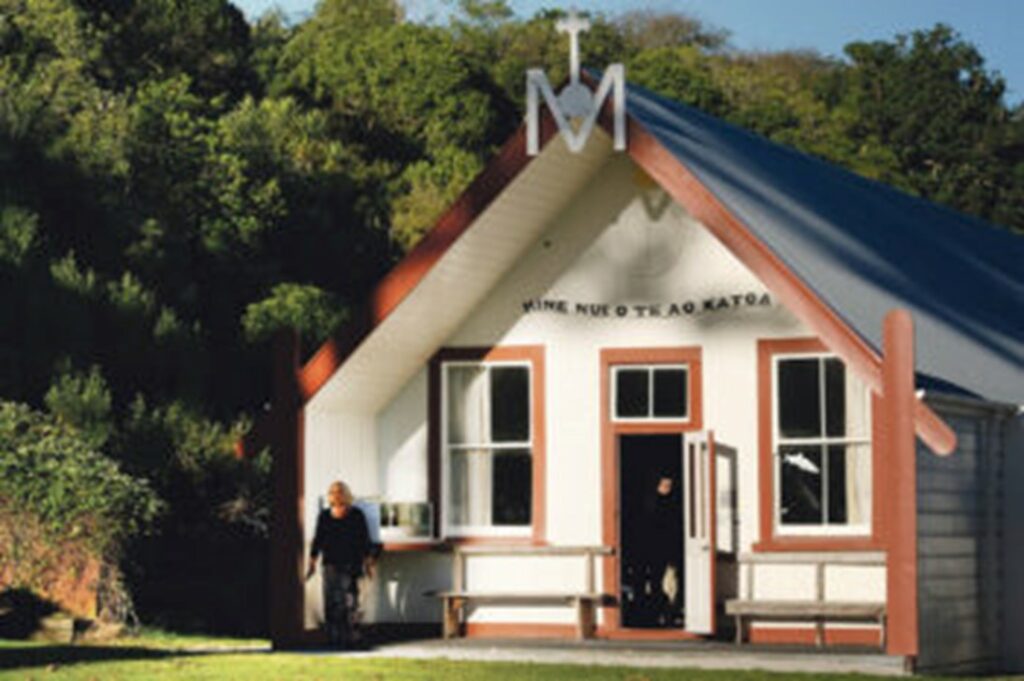

At Pukekaraka in the township of Otaki, an hour north of Wellington city, there lies a meeting house which shares its whenua (land) with the Catholic Church. Things are different at Pukekaraka. There is a meeting house (wharepuni) which has been there since 1905, and there is not a carving in sight! The meeting house follows the same design as wharepuni throughout the country, however the whare is bereft of carvings. The name of the meeting house is “Hine nui o tea o katoa”, and in the name is the reason for no carvings. Translated the name means ‘Mother of all the world’. In other words, no one iwi (tribe) or whanau (family) can lay claim to Mary as “our” ancestor. She (Mary) does not belong to us, we belong to her! What I find of great interest here is that the Marist Maori Mission was established at Otaki in 1841. In 1894 the Sisters of St Joseph had established a school there to teach (and board), local children. The whare was built in 1905. Within 60 years the local people had a sense of Mary belonging to everyone, “ o tea ao katoa”.

Ko Hāta Maria, te Matua Wahine o Te Atua

In Aotearoa – New Zealand, in Māori culture, meeting houses (whare nui or whare puni) are symbols of tribal prestige and are often named after, and seen as the embodiment of, a tribal ancestor. The structure itself is seen as an outstretched body, with the roof’s apex at the front of the house representing the ancestor’s head. The main ridge beam represents the backbone, the diagonal bargeboards which lead out from the roof are the arms and the lower ends of the bargeboards divide to represent fingers. Inside, the centre pole (poutokomanawa) is seen as the heart, the rafters reflect the ancestor’s ribs, and the interior is the ancestor’s chest and stomach. Whare are richly carved, and these carvings will be particular to the local tribe (iwi), and will declare “this is our house.”

At Pukekaraka in the township of Ōtaki, an hour north of Wellington city, there lies a meeting house which shares its whenua (land) with the Catholic Church. Things are different at Pukekaraka. There is a meeting house (wharepuni) which has been there since 1905, and there is not a carving in sight! The meeting house follows the same design as wharepuni throughout the country, however the whare is bereft of carvings. The name of the meeting house is “Hine Nui o te Ao Katoa”, and in the name is the reason for no carvings. Translated the name means ‘Mother of All the World’. In other words, no one iwi (tribe) or whanau (family) can lay claim to Mary as “our” ancestor. She (Mary) does not belong to us, we belong to her! What I find of great interest here is that the Marist Māori Mission was established at Ōtaki in 1841. In 1894 the Sisters of St Joseph had established a school there to teach (and board), local children. The whare was built in 1905. Within 60 years the local people had a sense of Mary belonging to everyone, ‘o te ao katoa’.

On the 15th of August, 2021, at the initiative of the New Zealand Bishops’ Conference, the country of Aotearoa/New Zealand was rededicated to Our Lady Assumed into Heaven. The country was originally dedicated by Bishop Jean Baptiste Pompallier when he celebrated the first Mass on the whenua known as Aotearoa on 13th January 1838. Mary, the mother of Jesus, was never a Roman Catholic, we have however laid claim to her and made her ours! This rededication is not a rededication of Catholic New Zealand; that was not Bishop Pompallier’s intention, nor is it the intention of our present Bishops. This is a rededicating of our land and its people to the care of Mary, the Mother of God. Pukekaraka is the birthplace of the Church of Wellington so it is fitting Ko Hāta Maria, Te Matua Wahine o Te Atua [Mary, Mother of God] began her journey (Te Ara a Maria) at Pukekaraka.

This Sunday, August 14th, our Church is invited to celebrate the Feast of the Assumption. This celebration will coincide with a Mass of Dedication of St Mary of the Angels Wellington as the National Shrine to Mary, Mother of God, Assumed into Heaven. This concludes the year-long hīkoi (journey) of the specially commissioned artwork throughout the country’s six dioceses.