This Sunday’s Gospel from St Luke (10: 38 – 42) recalls for us the story of Jesus visit to the house of Martha and Mary. Some no doubt will immediately take the line that Martha was the active type and Mary the passive or contemplative type, and that Jesus is simply affirming the importance of both and even the priority of devotion to him.

That devotion is undoubtedly part of the importance of the story.

However, there is more in the story; a brave preacher may offer a reflection on rule-flouting!

Far more obvious to any first-century reader, and to many readers in Turkey, the Middle East and many other parts of the world to this day would be the fact that Mary was sitting at Jesus’ feet within the male part of the house rather than being kept in the back rooms with the other women. This, I am pretty sure, is what really bothered Martha; no doubt she was cross at being left to do all the work, but the real problem behind that was that Mary had cut clean across one of the most basic social conventions. It is as though, in today’s world, you were to invite me to stay in your house and, when it came to go to bed, I was to put up a camp bed in your bedroom. We have our own clear but unstated rules about whose space is which; so, did they. And Mary has just flouted them. And Jesus declares that she is right to do so. She is ‘sitting at his feet’; a phrase which doesn’t mean what it would mean today, the adoring student gazing up in admiration and love at the wonderful teacher. To sit at the teacher’s feet is a way of saying you are being a student, picking up the teacher’s wisdom and learning; and in that very practical world you wouldn’t do this just for the sake of informing your own mind and heart, but in order to be a teacher, a rabbi, yourself. A position entirely unthinkable for a woman in the social order of Jesus’ time.

Each of these preaching stances is valid.

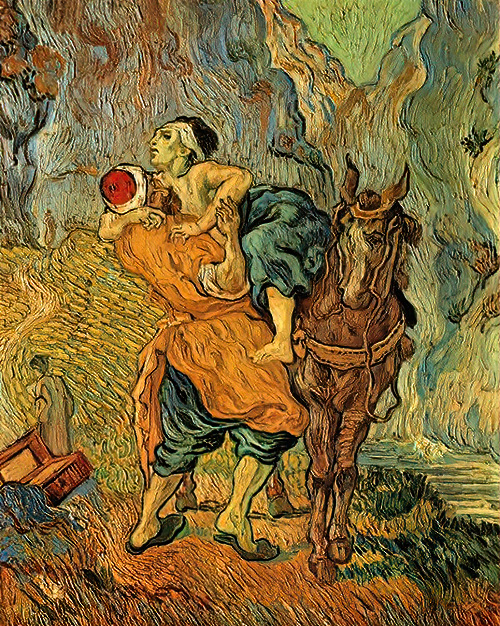

I am going to suggest a third, and it is imaged for me in the painting I have chosen by the Dutch artist  (1632 – 1675). Vermeer is best known, surely, for his painting titled “Girl with the Blue Earring”, and his works are among the greatest treasures in the world’s finest museums. Vermeer began his career in the early 1650s and one of his earliest works is a large-scale biblical scene with the title “Christ in the House of Martha and Mary”. The artwork dates from 1654 and hangs in the National Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland.

(1632 – 1675). Vermeer is best known, surely, for his painting titled “Girl with the Blue Earring”, and his works are among the greatest treasures in the world’s finest museums. Vermeer began his career in the early 1650s and one of his earliest works is a large-scale biblical scene with the title “Christ in the House of Martha and Mary”. The artwork dates from 1654 and hangs in the National Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Vermeer’s representation of the theme is focused totally on the three figures. Christ, because of his gesture and the soft glow that radiates from his head, is the dominant figure. Martha leans over to hear his words while Mary sits by his feet, her head resting on her hand.

There is an intimacy of persons in the scene; they obviously know each other well; the relaxed pose of Jesus and his comfort around women is evident. This may well be a lesson for us men, and especially clergy, today, namely to grow in our relationship with women from a position of equality. In Vermeer’s painting, the relaxed posture of Jesus only makes sense because of the presence of Martha and Mary. Jesus is bodily present to each of them. All three are in the same room, and in a sense occupy the same space in an acknowledging and relaxed way. There does not appear to be any competition for superiority in their stance.

Also, Vermeer has both women in a poise of listening – we sometimes have a busy Martha, running around in the kitchen with pots clanging and the fire-spitting in the range!

There is, too, a small detail, within the text, that, at times we can overlook, “Now as they went on their way, he entered a certain village, where a woman named Martha welcomed him into her home.” (10:38). Did you spot it? ‘Welcomed him into her home’ – the home belonged to Martha! Our growing into a personal, intimate relationship with Jesus begins with our ‘welcoming [him] into our home’!